Technology

This is how FoodCourt’s ‘dark kitchens’ work

A growing number of startups are running delivery-only kitchens that eliminate dining rooms and front-of-house staff. These dark kitchens, sometimes called cloud, “ghost” kitchens, or virtual restaurants, are designed for two primary goals: lower costs and speed. FoodCourt, a Y Combinator–backed ...

TechCabal

published: Sep 02, 2025

A growing number of startups are running delivery-only kitchens that eliminate dining rooms and front-of-house staff. These dark kitchens, sometimes called cloud, “ghost” kitchens, or virtual restaurants, are designed for two primary goals: lower costs and speed.

FoodCourt, a Y Combinator–backed company, is one of the key players in the Nigerian market. The startup owns its brands, kitchens, and app, giving it control of costs and quality as it expands beyond Lagos and Abuja. It has also become a rare case among cloud kitchen startups that can generate $1 million in annual revenue per location.

How does FoodCourt work?

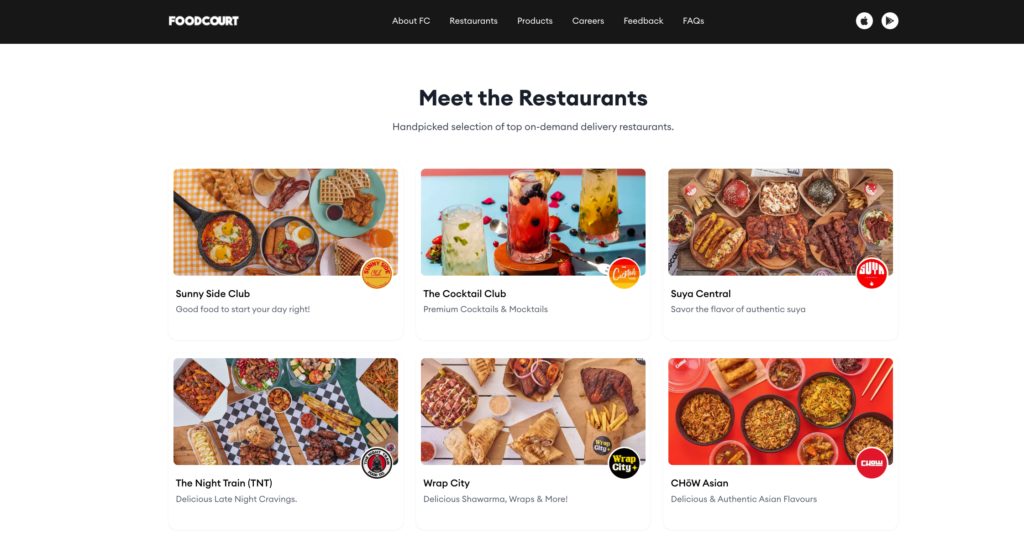

FoodCourt is an online delivery platform with a smartphone application. On the customer-facing side, customers browse different restaurant brands on the FoodCourt app and add items from several menus to a single basket.

Image Source: FoodCourt

Once a customer checks out, the order goes straight to a digital display that routes items to the right stations. Meals are prepared, consolidated, and packed.

“When you download our app from the Play Store, you’ll see all the virtual restaurants we own, each with its own name and brand identity,” Henry Nneji, CEO and co-founder at FoodCourt, told TechCabal. “You can browse through the menus and add items from different restaurants into one basket. For example, if a family wants Chinese food, native dishes, and burgers with fries, everything can arrive in a single order. That’s one of our superpowers.”

FoodCourt does not employ riders but partners with last-mile delivery providers working under service agreements to deliver food to its customers.

Inside the kitchen

The process of opening a new kitchen begins with audience analysis according to Nneji. Consumer tastes, price points, and demographics determine the brands that will be launched in that location.

Site selection is influenced by logistics such as road networks, proximity to filling stations and marketplaces, and the distance from existing kitchens. “We look at the road network, closeness to filling stations, marketplaces, and the distance from our other locations nearby,” Nneji said.

Once a space is secured, the kitchen is designed for efficiency, and new brands are created to match local demand and spending patterns.

FoodCourt produces most of what it sells. Bread, juices, and sauces are made in-house, both for its own brands and for other businesses under contract manufacturing arrangements.

Grocery deliveries are coming back

FoodCourt ran a short grocery pilot using a dark-store model. It stocked goods in-house so customers could add groceries to a meal order. The company ended the pilot and shifted resources back to prepared meals. It also grew B2B lines, including corporate meal services, and began selling its bread and juices to retailers.

Nneji added that management has been weighing a return to groceries via aggregation rather than holding inventory. The plan is to pull from external suppliers across fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) and electronics to widen choice without stocking products itself.

“Over the next couple of months, we are looking at revisiting the grocery delivery space. However, we’re looking at aggregating rather than the dark kitchen model for groceries,” Nneji clarified.

It is a Lagos and Abuja affair, for now

FoodCourt is focusing on Lagos, where its central kitchens act as hubs serving the city’s main districts. The company plans to add “micro locations” across Lagos to reach smaller neighbourhoods and bring delivery closer to customers, Nneji told TechCabal. Despite doubling down on Lagos and Abuja, the company expects to explore new African markets within the next year.

“Our current central kitchens will serve as hubs, and we’ll operate several micro locations across Lagos so we can get to the nooks and crannies and really be close to all the consumers,” Nneji said.

The rebranding question

Speculation around FoodCourt’s identity dates back to its YC debut in 2022. Nneji said there was never a rebrand. Co-Kitchen Workspace Limited is the registered Nigerian entity, while FoodCourt is the business name.

When applying to Y Combinator, Nneji initially used the company’s registered name, Co-Kitchen, before updating the application to reflect its trading name, FoodCourt. The business continues to operate under the brand FoodCourt, while its legal entity remains Co-Kitchen Workspace Limited in Nigeria.

“We’ve always operated as FoodCourt. To this day, our registered name in Nigeria is still Co-Kitchen Workspace Limited, doing business as FoodCourt,” Nneji clarified.

Scaling is hard

Running several kitchens raises issues around staff and quality. In May 2024, FoodCourt laid off nearly 100 employees after redesigning its cooking processes. The company said the changes were aimed at cutting preparation times and improving consistency. Larger kitchen equipment was introduced, and many ingredients began to be prepped ahead of orders.

Chef Tilewa Odedina, who manages the kitchens, said at that time that the goal was to reduce meal preparation time to 20 minutes for its 10,000 active monthly customers. But the optimisation remains a work in progress, with complaints about late deliveries still surfacing online.

“The bottleneck is people management and consistency,” Nneji said. FoodCourt is standardising operations early to avoid problems as it grows. Meals are closely controlled so that packaging, recipes, and prep times are the same in Abuja and Lagos.

FoodCourt lists some of its brands on other delivery apps, but only for visibility. Not all restaurants are included, as the startup wants to avoid dependence on aggregators, possibly to maintain control over sales channels and brand identity. In July 2024, it struck a deal with Chowdeck to make some of its brands available on the platform. TechCabal learned at the time that Chowdeck offered FoodCourt advertising spend, similar to an agreement it had earlier with Chicken Republic.

“We work with them, but our business models are different,” Nneji said.

Nigerians are increasingly ordering meals online. The online food delivery market is thus expanding, valued at over $1 billion in 2024 and projected to more than double by 2033.

FoodCourt generated revenue before joining Y Combinator and reported a significant sales boost during the programme. In early 2024, the company raised $1.7 million. Its average order value is ₦15,000, and it claims to be profitable, though it has not shared detailed figures.

Local conditions strengthen the case for cloud kitchens, considering consumers are sometimes willing to pay for convenience, despite inflation and retail costs remaining high in Nigeria. Investors see opportunity since Nigeria’s food delivery market is expected to reach $2.4 billion within eight years, despite economic pressures.

Mark your calendars! Moonshot by TechCabal is back in Lagos on October 15–16! Join Africa’s top founders, creatives & tech leaders for 2 days of keynotes, mixers & future-forward ideas. Early bird tickets now 20% off—don’t snooze! moonshot.techcabal.com