General

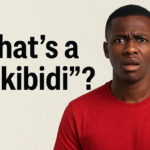

New Words enter the Dictionary, and Ghanaians ask, “What’s a ‘Skibidi’?”

The English language is always changing, and now a major dictionary has made the increasing use of social media terms official. The Cambridge Dictionary has added over 6,000 new words to its online edition, many from TikTok trends and viral videos. Words like “skibidi,” “delulu,” and “tradwife” a...

MyJoyOnline

published: Aug 21, 2025

The English language is always changing, and now a major dictionary has made the increasing use of social media terms official. The Cambridge Dictionary has added over 6,000 new words to its online edition, many from TikTok trends and viral videos. Words like “skibidi,” “delulu,” and “tradwife” are now part of the global lexicon. However, for many Ghanaians, these new words may seem like gibberish.

Their inclusion highlights a significant shift: internet trends are now influencing language on a global scale. As Colin McIntosh, the dictionary’s lexical program manager, notes, “It’s not every day you get to see words like skibidi and delulu make their way into the Cambridge Dictionary.” This statement, however, highlights a divide. While these terms may be gaining traction in the West, they have not yet fully permeated everyday conversation in Ghana. These words aren’t emerging from local, shared experiences but are being pushed globally by algorithms. This raises critical questions about what truly constitutes a “global” word.

Decoding the Digital Dictionary

The new dictionary words are often linked to specific internet phenomena. “Skibidi,” for example, comes from “Skibidi Toilet,” a viral YouTube series that has racked up billions of views. The Cambridge Dictionary defines it as “a word that can have different meanings such as ‘cool’ or ‘bad,’ or can be used with no real meaning as a joke.”

An example of its use in a sentence: “that wasn’t very skibidi rizz of you.” This phrase is often used online to mean “that wasn’t a very smooth or charming move.”

Similarly, “Delulu,” a play on “delusional,” emerged to criticize obsessive K-pop fans. It has since become a more general term for believing things that are not true. It was brought into the offline mainstream in March when Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese dropped the phrase “they are delulu with no solulu” during a speech in Parliament, after two podcast hosts dared him to use it.

Albanese said, “They are delulu with no solulu, Mr Speaker. They are completely delusional, completely delusional, Mr Speaker, when it comes to that.”

Other new words include “broligarchy” and “tradwife.” “Tradwife,” an abbreviation of “traditional wife,” is a term used to describe a controversial social media trend where women embrace traditional gender roles and homemaking. The word “broligarchy,” a mashup of “bro” and “oligarchy,” referenced the tech giants who attended US President Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2025. This phenomenon also extends to existing words; for instance, “snackable,” once only for food, now describes easily digestible online content. The phrases “red flag” and “green flag,” while not new words, have been given new meanings in the dictionary. “Red flag” is now used to describe an undesirable quality in a partner, while “green flag” is used to express a desirable quality. These changes prove that language is fluid and responsive to new digital cultures.

Local Slang Versus Global Trends

In Ghana, local languages and slang evolve organically from its culture and experiences. As Dr. Kofi Agyekum, a Professor of Linguistics at the University of Ghana, notes in his academic work, “The Ghanaian linguistic experience is a contest of wits, of speaking without saying, and of engaging in obliqueness and implicitness.”

This perspective explains why new words from abroad don’t always resonate. As Kwabena Mensah, a student at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, put it, “I’ve heard ‘delulu’ on TikTok, but I wouldn’t use it in a conversation with my friends. It doesn’t feel natural. Our own words, like ‘eish’ or ‘chale,’ express things these new words can’t.”

Baaba Dadson, a high school student in Cape Coast, echoed this, stating, “Our slang is a reflection of our unique Ghanaian experience, not an animated toilet series.”

The inclusion of these words in a major dictionary is a powerful symbol of a new era. It’s a testament to the influence of Western internet culture, but it does not mean these words have become universal. Language is tied to identity and culture. While the world may be talking about “skibidi,” our words continue to tell our own story. This new trend highlights the importance of staying aware of global linguistic shifts while also cherishing and protecting the local slang that makes our conversations uniquely Ghanaian. Essentially, language is not just what we say—it’s who we are.

Read More