General

Dealing with the challenge of urban renewal through the lenses of Nairobi and Accra

A national assignment brought me to Kenya a couple of days ago. Upon my arrival in Nairobi last Tuesday, I was privileged to lodge in the Concord Hotel and Suites in the middle of Parklands, an Indian-filled community of Nairobi. One observation that struck me during my stay was the scourge of ge...

MyJoyOnline

published: Aug 18, 2025

A national assignment brought me to Kenya a couple of days ago. Upon my arrival in Nairobi last Tuesday, I was privileged to lodge in the Concord Hotel and Suites in the middle of Parklands, an Indian-filled community of Nairobi. One observation that struck me during my stay was the scourge of gentrification. All through my rounds of the neighbourhood, it was very apparent that deliberate steps were being taken to replace the middle-level to high-end bungalows built during the colonial and early years of the country’s independence period with high-rise residential apartments, among others.

Just so the ordinary person can be on the same page as the real estate practitioners. Gentrification (sometimes referred to as urban renewal, though not exactly the same) is typically the process by which a neighbourhood is transformed from low value to high value. It is also viewed as a process of urban development during which a community or segment of a city is facilitated through urban renewal schemes, to have it develop rapidly within a very short period.

Historically, the term ‘gentrification’ was derived from the word ‘gentry’, which referred to people of a higher social status. In the United Kingdom, for example, the term ‘landed gentry’ was initially in reference to owners of land who could live off the rental incomes obtained from their properties.

Subsequently, gentrification became popularised by a British Social Scientist (Ruth Glass) in 1964 when she used the terminology about the influx of middle-class dwellers into London’s working-class communities and thereby displacing those who were previously occupying those communities.

It is interesting to note that many cities around the world have since experienced the scourge of gentrification. Most of the time, this has had a direct impact on the dynamics of the housing market. In many of our cities, some communities that previously did not attract any excitement all of a sudden became vibrant neighbourhoods with plush apartments, condominiums, offices, entertainment outlets, restaurants, malls and other expensive retail outlets, coffee shops, etc.

Gentrification has, over time, developed into a complex social matter that end up with both benefits and challenges. While young families get the opportunity of acquiring reasonably priced homes in a safe community, usually within the city centre, with wonderful social amenities and services. While this happens, the various local authorities also benefit from the collection of higher taxes on hugely improved property values and increased economic activity on these facilities.

Unfortunately, over time, the neighbourhood’s original dwellers usually end up being displaced as a result of escalated rents and a higher cost of living that they are mostly unable to cope with.

In my engagements with my tour guide and a few materials I discovered, gentrification in Kenya is pretty much heavy in cities like Nairobi and Kisumu, characterised by the influx of wealthier residents and businesses into previously low-income areas. One huge concern that gentrification brings is the challenge of social equity and the displacement of vulnerable segments of the population.

From my observations and information gleaned from a couple of colleagues in the real estate industry Nairobi, it does appear that beyond the earlier outcomes indicated, gentrification displacement of residents from their original neighbourhoods, gentrification often leads to a shift in the social and cultural landscape of a community, with the influx of new residents and businesses more often than not completely changing the face, character and identity of the area. At times, policy interventions such as rezoning have also played a significant role in shaping gentrification processes, whether positively or negatively.

Information gleaned indicates that significant gentrification in Kenya has largely been felt in the Parklands, Eastleigh and Upper Hill communities of Nairobi, as well as the city of Kisumu, which have all witnessed high-rise developments and ultimately pushed up property values and rent. A Housing Administration student at the University of Nairobi, whom I spoke with at the Museum of Illusion, was gravely worried that neighbourhoods that were once very nice and quiet residential suburbs.

He listed Parklands, Koleleshwa, Lavington, Mathare, and Kilimani as decent communities that had now been packed with dense urban slums, something he considered as being extremely depressing. In his view, there was no urban planning, but simply the development of massive apartments being built everywhere without commensurate upgrades in public services. To him, what’s being witnessed was more of ‘ghettofication’. In the Kibera neighbourhood, a slum upgrading project meant to provide affordable housing and infrastructure to the citizens appears to rather end up creating a displacement challenge due to affordability concerns.

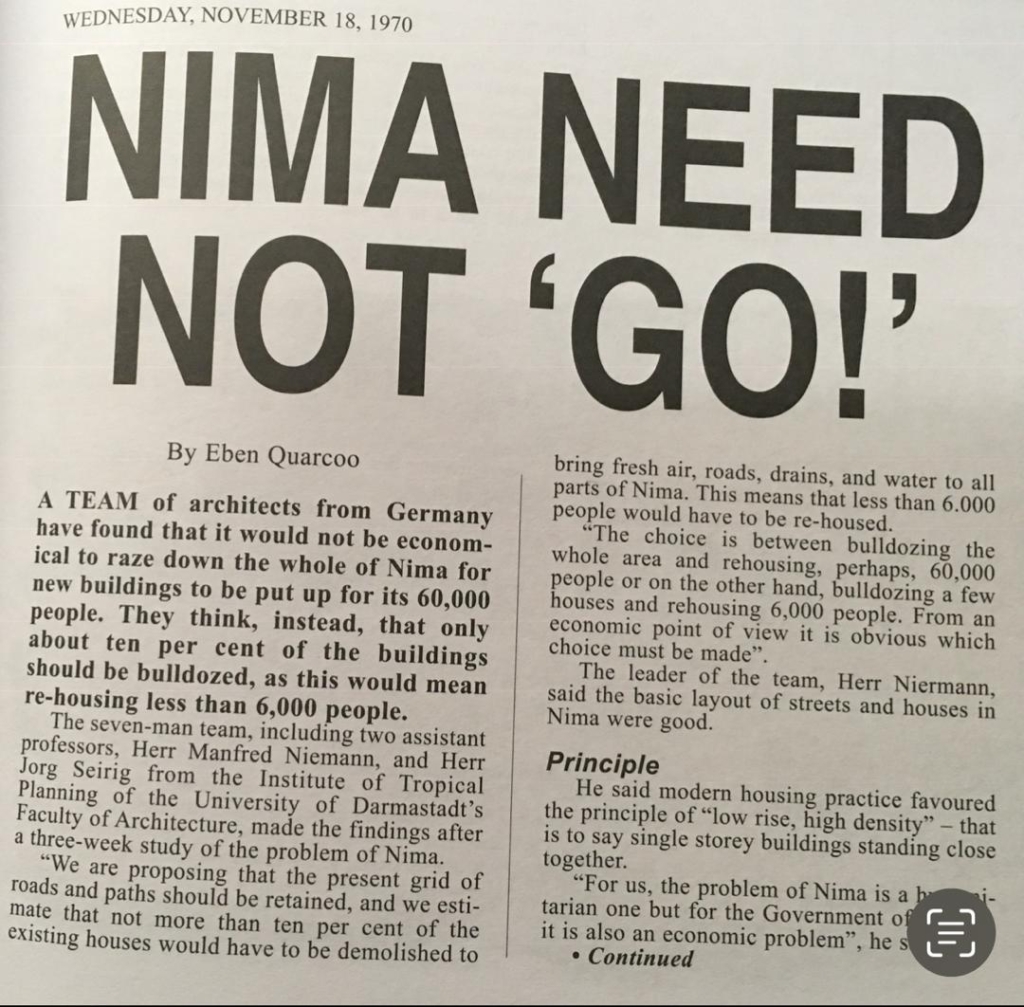

The challenge of gentrification is certainly not limited to Nairobi but affects many cities across the world. In the city of Accra, too, re-zoning of the Ridge Ambassadorial Enclave, Cantonments, North Labone Estates, Roman Ridge, through the Accra Redevelopment Scheme from the late 1990s into the mid 2000s saw a wave that led to the gradual conversion of these very fine government residential neighbourhoods into heavily mixed-use communities.

The effects of those developments are now beginning to show up. These communities are now grappling with the challenges of noisy communities, vehicular traffic and nuisance, environmental concerns, social vices, among others. It will not be surprising to witness in the near future that the reason for which the various developers scrambled for lands in these localities will become the very reason that will push them out again.

While that scheme had almost failed, the government, through the Land Use and Spatial Planning Authority (LUSPA), introduced the Greater Accra Master Plan in 2019. That GAMA Plan 2040 seeks to develop and implement a comprehensive urban renewal plan aimed at modernising the city of Accra and improving its living conditions. Some of the key aspects include developing infrastructure, creating affordable housing, and revitalising the city’s central business district. This plan also emphasises economic empowerment initiatives, particularly for young people, and the development of recreational and cultural spaces.

Generally, gentrification most of the time raises concerns about social equity and the displacement of vulnerable populations. Pete Saunders, an urban planning expert who is considered an authority on the subject matter, has laid out some ground rules for understanding the trend of gentrification. In an email to HuffPost Home, Saunders wrote, “Because some cities have had historically lower black populations, less of the city has become invisible to current residents. This means that more of the city became ‘available’ for potential future gentrification”.

Clearly, as cities develop, there is a need to undertake some forms of urban renewal. In doing this, it is very important that our policymakers and implementers drive this by outlining the vision for the policy of urban renewal, setting out the supportive policies, facilitating investment in that direction, and ensuring equitable outcomes. They also create the framework for the successful renewal by addressing economic, social, and environmental aspects of the redevelopment of urban spaces. However, the way and manner by which this process is managed is as critical as the thought itself.

It is something that both of our leaders within the policy space, as well as those in the real estate industry, will have to do a critical job introspection and find a lasting solution to.

We certainly cannot continue this way!

Engr Eric Atta-Sonno

[email protected]

Accra