Technology

Africa’s tech ecosystem must break free from digital feudalism

A quiet but profound struggle is playing out within Africa’s tech ecosystem—one not over code or innovation, but over control. It is the battle for digital sovereignty: the right of African nations to own their digital infrastructure, govern their data, and shape the future of their technological...

TechCabal

published: Aug 08, 2025

A quiet but profound struggle is playing out within Africa’s tech ecosystem—one not over code or innovation, but over control. It is the battle for digital sovereignty: the right of African nations to own their digital infrastructure, govern their data, and shape the future of their technological ecosystems. Yet as it stands today, much of Africa’s digital success story rests on a fragile foundation built not on autonomy but dependency. And if we’re not careful, what we are hailing as a digital transformation may turn into a new chapter of digital feudalism.

In this new digital order, global technology giants control the platforms, own the infrastructure, and extract the value, while African governments, startups, and citizens rent access to systems they neither designed nor can meaningfully govern. For all our innovation and growth, we remain tenants in someone else’s house.

Access without agency

It’s easy to be dazzled by the vibrancy of Africa’s tech scene. Nigeria’s unicorns—Flutterwave, Andela, and Moniepoint—have made international headlines. Kenya’s Silicon Savannah has redefined mobile finance through M-Pesa. Egypt has emerged as a fintech and e-commerce hub in North Africa. But beneath this success lies a sobering truth: we don’t own the pipes.

Take Nigeria, where federal ministries and universities rely on Microsoft’s cloud to run their operations. Public biometric data, national IDs, and educational platforms are hosted on foreign servers—often beyond the reach of Nigerian law. Despite the 2023 Data Protection Act, most of this infrastructure remains externally owned and governed. Nigeria’s burgeoning digital identity system may empower service delivery, but without true data sovereignty, it risks becoming another extractive tool, where Nigerian data fuels AI models and analytics from which Nigerians gain little benefit.

In Kenya, M-Pesa has been a revolutionary force. Yet many forget that it was developed not by Kenyan engineers, but by Vodafone UK in partnership with Safaricom. The IP and core infrastructure remain abroad. Kenya’s data protection law (2019) is promising, but enforcement remains weak and foreign platforms dominate digital transactions, communications, and content consumption.

In Egypt, we see rapid digital expansion: smart cities, digitised health systems, and artificial intelligence strategies. However, many of these projects are being implemented through Chinese and European partnerships, where the core technologies, platforms, and data hosting remain outside Egypt’s control. Telecom Egypt’s collaboration with Huawei underscores a wider trend: outsourcing infrastructure without long-term guarantees of national ownership.

What unites these cases is a fundamental imbalance: Africans are connected, but not in control.

Infrastructure must create value, not just extract it

We would never dream of outsourcing our roads, ports, or hospitals without legal safeguards and local benefits. Yet we hand over control of digital infrastructure—the backbone of our economies—with little more than a handshake or memorandum of understanding.

We must change that. Digital infrastructure is public infrastructure. And just like roads and power grids, it should serve the public good, create local jobs, protect rights, and build institutional capacity. Yet too often, it is built and owned by outsiders, governed by foreign laws, and monetised for offshore shareholders. This is not innovation; it is dependency in disguise.

Sovereignty is not repression

To be clear, digital sovereignty does not mean state control or internet shutdowns. Some African governments have misunderstood this principle, weaponising it to surveil activists, censor dissent, or block platforms under the guise of national security. That’s not sovereignty, that’s authoritarianism wearing digital camouflage.

True digital sovereignty is about empowering citizens. It means having the infrastructure, skills, and policies to ensure African data works for African development. It means protecting the digital rights of citizens—privacy, freedom of expression, and access to information—whether the threat comes from Big Tech or Big Brother.

AI: The next frontier of exploitation?

Artificial Intelligence is quickly becoming the engine of global power. From medical diagnostics to financial modeling, these systems are trained on vast datasets, including African text, images, and voices. Yet most African countries don’t know how their citizens’ data is used in global AI training pipelines. Worse still, they have no legal power to challenge biased systems that may reinforce inequality.

We risk being digitally colonised not just by platforms, but by algorithms: AI systems trained elsewhere, governed elsewhere, and deployed here without accountability. This is why local investment in AI must be a continental priority. Nigeria’s National Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Egypt’s AI strategy are commendable. But they are not enough. We need local datasets, African language models, open-source alternatives, and ethics frameworks rooted in our values.

What a people-centered digital ecosystem looks like

The good news is that change is possible. Senegal is building a national data center in Diamniadio to host government services locally. Rwanda’s Irembo platform delivers over 100 public services online while keeping citizen data under national jurisdiction. These are models we must scale, not exceptions we admire.

Africa also needs stronger regional regulation. The African Union’s Data Policy Framework and the Smart Africa Alliance are important steps, but they need teeth: shared standards, joint infrastructure projects, and enforcement mechanisms. We must stop acting like 54 disconnected markets and start thinking like a single digital bloc.

The road ahead

Africa’s tech ecosystem is at a fork in the fiber-optic road. We can continue down the path of digital feudalism where our innovation is leased, our data exported, and our digital futures outsourced. Or we can choose the harder, bolder path of digital sovereignty—owning our infrastructure, governing our platforms, and protecting the digital rights of our people.

Yes, it will require regulation, investment, coordination, and imagination. But it is the only path that ensures our digital future is built by us, for us.

The servers are humming. The data is flowing. The platforms are expanding. Now we must ask ourselves: Will they serve Africa, or will Africa continue to serve them?

________

Faiz Muhammad is the Executive Director of Blue Sapphire Hub, leading innovation and enterprise development across Africa’s Sahel region. He champions digital inclusion, startup growth, and policy reform to drive sustainable, tech-enabled development.

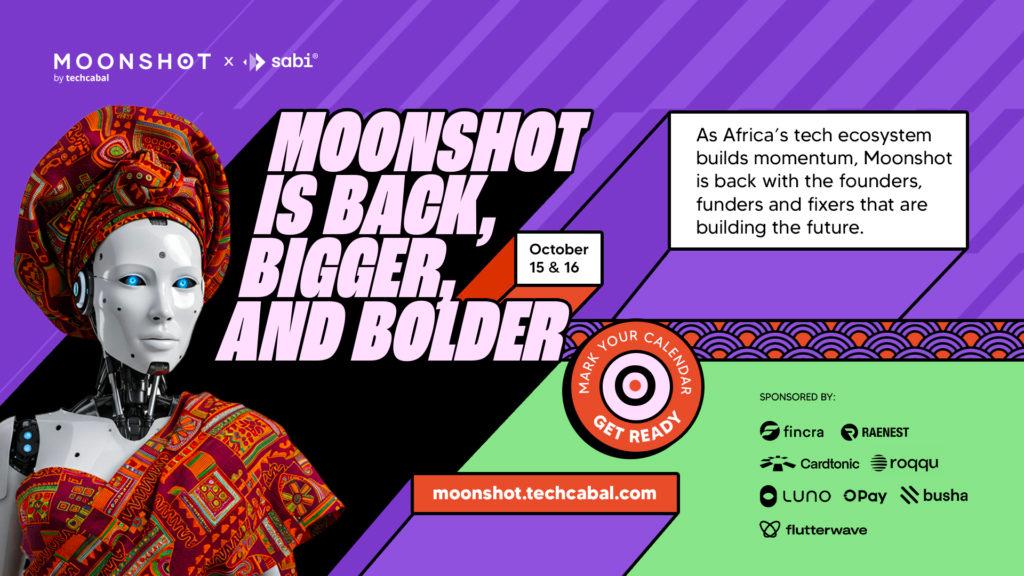

Mark your calendars! Moonshot by TechCabal is back in Lagos on October 15–16! Join Africa’s top founders, creatives & tech leaders for 2 days of keynotes, mixers & future-forward ideas. Early bird tickets now 20% off—don’t snooze! moonshot.techcabal.com